PROTECT YOUR DNA WITH QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY

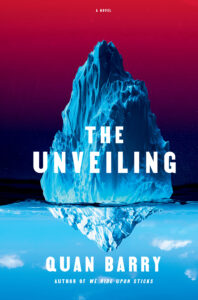

Orgo-Life the new way to the future Advertising by AdpathwayQuan Barry is an award-winning playwright (and poet) as well as a novelist, skills which show in the virtuosity of the ensemble of characters she has created in The Unveiling. Her primary narrator Striker, a Black film scout booked on a luxury cruise to Antarctica to seek out locations for a movie about the explorer Ernest Shackleton, has a sharp, sophisticated point of view, and a double consciousness, toggling between her perceptions of her fellow travelers and their attitudes about people of color, and the inner self who is slowly emerging into her awareness as childhood memories of her beloved sister Ama surface.

Then there is Lucy and her three dads, the photographer whose camera is shattered by an albatross, unleashing echoes of “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” (the bird believed to house “the souls of sailors lost at sea”); the Tech Titan and his wife, the Grande Dame and her husband the Baron, with Alexie and Vadim, their “beefy Russian muscle;” Taylor and Kevin, whose marriage might be saved by this journey; Billy Bob and Bobbi Sue and their kids, Anders and Mikey, the crew, the ghosts of explorers, seal hunters and doomed ship crews past. The Unveiling begins with a kayaking trip on Christmas Eve. A sudden collective mishap occurs (“The feeling of falling off a cliff,” as Striker puts it). As the narrative continues, mistakes are made. Betrayals happen. Vicious birds attack. Vicious humans attack. Memories change the future.

The Unveiling, with its icy twists and deep blue horrors, is a blend of wrought historic layers and contemporary anxieties. What was its origin story? I asked Barry. Did she visit the Antarctic landscapes with twenty-four-hour sunshine she describes in lyrical, sometimes terrifying detail? Did she see the icebergs calving steadily due to climate change, elephant seals, penguins, volcanos, hot springs, the ruins of early explorers’ huts?

“First off, I’m beyond lucky to have traveled to many distant and fascinating places,” she explained via email. “Somehow I’ve been to all seven continents though since the pandemic I’ve mostly been stateside (I think I’ve exhausted my wanderlust, which is both fine by me and probably better for the planet). But back in 2004 when I was still burning both ends of the travel candle, I went on a twelve-day cruise to Antarctica over the Christmas holiday on the Akademik Iofee, an expeditionary ice vessel that the Russians used to conduct research in the polar regions during Soviet times.

So yeah, I was fortunate to see many of the things that are described in the novel, e.g. while kayaking, I actually witnessed a leopard seal kill a penguin up-close by smashing it back and forth on the surface of the ocean like a dog toy (I’d never realized how much water and concrete had in common). When I came back to the States, I wrote a couple of poems about Antarctica admittedly mostly out of guilt (I felt like I had to have something to show for all that) and then filed the trip away in my memory banks. That’s what I do when I go somewhere—I never knowif and when a landscape might appear in my work. I go just to hang out and eat and walk around and observe how the sunlight works in a different corner of the globe, and then an idea often appears to me from out of the blue many years later. The same thing happened in Mongolia. I was there in 2008 and then 2022 I published a book set in that country. (When I’m Gone, Look for Me in the East.)

“Anyhoo, I’ve always been FASCINATED (lowercase won’t get it across) by William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, which I consider to be one of the great horror novels of all time though it’s maybe considered an adventure story—the scene where Simon chats up the severed pig’s head is beyond creepy. So for a while I’d been kicking around the idea of writing a modern-day Lord of the Flies set in Antarctica, just a good ole-fashioned survival yarn. Then George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis. Suddenly I realized the story I envisioned could be (and should be!) much bigger, and I felt that as a BIPOC writer, I could write a horror novel informed by core questions surrounding issues of social justice.

“Obviously, the movie Sinners hadn’t come out yet while I was working on my book, but there was a line in a semi-recent New Yorker profile of Ryan Coogler that said Coogler ‘has likened his role as a Black filmmaker to membership in a subset of artists freighted with knowledge of a fundamental social fault line.’ Exactly. As a multi-ethnic person raised by white parents, maybe I’m also ‘freighted’ with certain racial knowledge. Lord knows I have opinions!

“Stephen King once said (though I think he was quoting the writer Anne Siddons) there are no such things as haunted houses, only haunted people. Antarctica seemed like the perfect laboratory to test this out. America’s racial legacy doesn’t end at the boundaries of our country—as Americans, the wrongs of the past travel with us wherever we go whether we like it or not.”

*

Jane Ciabattari: When did you first learn of Ernest Shackleton’s expeditions and other explorations? What sources were most helpful in that research?

I think that the central journey in life involves the removal of one’s false mask, thus revealing our true selves to both ourselves and the world.

Quan Barry: Probably I’d known about Shackleton long before I went to Antarctica because of T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland and that eerie line, “Who is the third who walks always beside you?” which references Shackleton’s harrowing journey on foot across the mountains of South Georgia Island in search of rescue. The line is both sinister and spiritual in its implication that it’s Christ who walks always beside us, but it’s also like that famous image in Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House—sometimes we believe we’re holding the hand of a beloved, but then it turns out the hand actually belongs to something much darker.

A lot of the literature about Antarctica was written by early explorers. Two of the must-reads in the genre are The Worst Journey in the World by Apsley Cherry-Garrard (about hoofing into the interior of the continent in the dead of winter in search of emperor penguin eggs) and South by Ernest Shackleton (the title says it all). There are also some great contemporary books about the continent, like The Crystal Desert by David G. Campbell, who spent several summers in Antarctica, which helped me learn about the natural history of the landscape.

JC: How did you arrive at the book’s title? In your opening epigraph, you introduce W.E.B. Du Bois’ concept of Black Americans’ experience of living with a double consciousness which acts as a kind of veil caused by “a ubiquitous fracturing of society along racial lines;” in your acknowledgements, you include a passage from “The Minister’s Black Veil,” the 1836 short story by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Were there other titles you considered?

QB: Before I went to Antarctica, I did a deep dive reading various books about the continent. Somewhere I came across a quote from the widow of Robert Scott, the English explorer who died as he tried to be the first to reach the Pole. When his widow learned of his death, allegedly she simply said, “My God is godly.” How true! That was the title I always envisioned for the book. I love the mystery of it, the enormity of it. What else is there to say in the face of the ineffable? But several early readers didn’t dig it as deeply as I did, plus the phrase maybe doesn’t make most readers think: horror! My agent suggested I draw up a list of images and ideas that I associated with the book.

Seeing/perception is a big theme in the work, coupled with the idea that humans create personae, i.e. masks, that we wear out and about in the world much like the minister in Hawthorne’s mega-creepy short story. The central question is: at the end of the day, is the mask I put on to navigate through society really me? If not, then who am I? I’m very attracted to the Buddhist idea of non-self. I think that the central journey in life involves the removal of one’s false mask, thus revealing our true selves to both ourselves and the world.

JC: Why did you name the cruise ship the Yegorov? Was it after the Soviet military commander?

QB: In early drafts of the novel, I called the ship the Iofee, which was the name of the actual ship I traveled on. But this is a work of fiction (heh!), so I needed an easy-to-pronounce Russian name that western readers wouldn’t stumble over like you sometimes do in Tolstoy, e.g. which would you rather have to read: Yegorov or von Wintzingerode? (True, von Wintzingerode was a real historical German who shows up in War and Peace plus the dude has the word ZINGER in his name, but you get my drift.)

JC: What inspired the character of Lucy, the “creepy little kid,” who was adopted by Frank and Hector from an orphanage in “one of the former Soviet republics” and who Striker encounters in the opening scene?

QB: I’ve only seen Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ maybe once sometime around 1991 (though after writing that sentence, I just YouTubed the ending (powerful). And yet (even before YouTubing) I still vividly remembered the angel who accompanies Christ down off the cross and into the hallucination where he dreams of what his life might have looked like had he just been born plain old human and not the Son of God. The angel is played by a child who is physically the very definition of angelic (plus her British accent is way posh), and yet toward the end of the scene the child is revealed to be anything but. Kids are often messengers. Out of the mouth of babes. And yet, maybe the Scorsese angel-child is an angel. Yeah yeah, I know the kid is actually supposed to be the Devil, but a real angel might seem demonic because said angel would drop so much TRUTH on us that we would rather turn away from it lest we shatter.

JC: At the end of the first kayak outing, after witnessing a leopard seal devour a penguin, a terrible accident occurs that changes everything. You introduce this with an interlude of nearly twelve blacked-out pages (erasure), with occasional words in lightface italics, as if a voice remains. Striker comes back to awareness floating all alone on the “thirteen million square miles of bone-chilling blue” that is the Southern Ocean. How did this crucial scene evolve?

QB: My decision to redact portions of the novel came very very very late in the process of editing the book and just seemed right. At the end of the day, I’m really an instinctual writer. I don’t have a scholarly bone in my body, i.e., nothing in me vibes with literary analysis or criticism. At times, I wish I had that skill set, but I don’t, so c’est la vie. At its heart, my book is a novel about memory, about a character whose repressed memories of childhood are gradually returning for better or for worse. It just made sense to me that the reader should also share the experience of dissociation which often befalls traumatized people. So I went with it.

Additionally, I would say that the word trauma is not one I use lightly. It feels weirdly trendy and is used for all kinds of situations where it maybe really doesn’t apply, like not getting one’s order done right at Starbucks. Ultimately, is this a book about racial trauma? Hmmm…Maybe I want to believe the answer to that question is yes and.

JC: Your ending is surprising and satisfying. Did you have it in mind from the beginning, or did it develop as the story unfolded?

QB: I usually have some kind of spidey sense about what might happen at the end of something but writ large. At the end of a novel or play or even a poem I just have some inkling of where we’re going. But then as I get there, the specifics are often vastly different from what I had originally thought yet somehow they’re also still of a piece with my initial vision. The same is true in this book.

My book is a novel about memory, about a character whose repressed memories of childhood are gradually returning for better or for worse.

JC: Throughout the novel, various characters mention literary and film classics like Stephen King’s Skeleton Crew, Hitchcock’s The Birds, H.P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness, Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” Shirley Jackson’s Hangsaman, among others. In your acknowledgements, you give a nod to the influence of writers like Jackson and Hawthorne, and to books like William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, as you’ve mentioned, and King’s The Shining. Are there other books, classics or contemporary, you would add to this list?

QB: The Great God Pan by Arthur Machen. True, I get weirded out easily—I have no idea how I read so many Stephen King books as a teen, but The Great God Pan, written in 1894, thoroughly freaked me out one autumn night when I read it all in one sitting (it’s a novella). The ending maybe gets a little silly, but the first chapters where a scientist conducts a brain experiment on a young woman in order to allow her to see God is the stuff of my nightmares. And a book that I love that isn’t necessarily a horror book but is horrifying in a quiet way that builds to one of the most satisfying endings ever is Sarah Moss’s Ghost Wall. There, the horror is the patriarchy and the human obsession with looking to the past for meaning. It’s so good—I think it’s a perfect book.

JC: Why do you think speculative fiction/horror fiction are so appealing to readers today?

QB: All you have to do is tune into today’s news for ten minutes and there’s your answer.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

QB: Nothing, and it feels good! When I’m working on a long project, I don’t really read, so I can literally (and sadly) go for years reading only a handful of books for fun. Right now I have no idea what’s next—script, novel, poem—and I’m not sweating it. I do think the current political climate isn’t helping—part of me believes in the idea that the artist should document her time period (especially if it’s a genocidal era) in some meaningful way, and another part of me is like, I just wanna write a romance. Maybe I can square the two? Stay tuned!

__________________________________

The Unveiling by Quan Barry is available from Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·  French (FR) ·

French (FR) ·