PROTECT YOURSELF with Orgo-Life® QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY

Orgo-Life the new way to the future Advertising by Adpathway

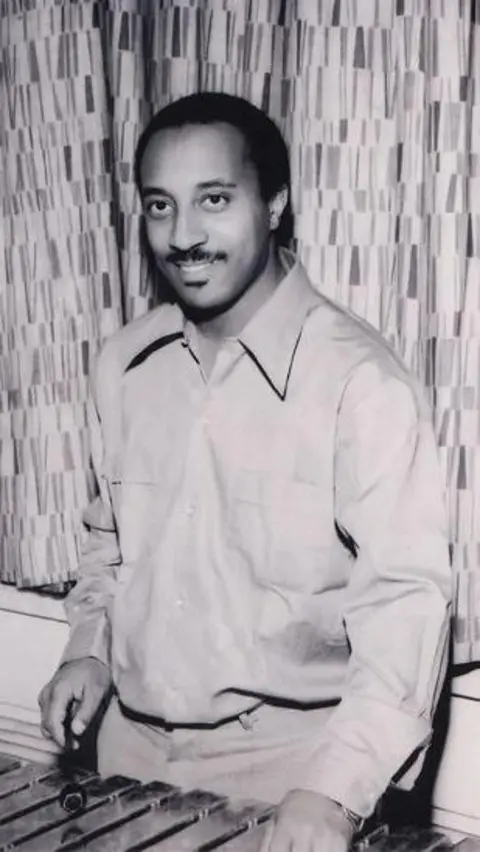

Mulatu Astatke

Mulatu Astatke

Ethiopian jazz musician Mulatu Astatke smiled as he held his arms aloft to acknowledge his audience for the last time.

Last month in London, the 82-year-old pioneer, who has done much to bring his blend of musical styles to the world, played his final live concert after a six-decade performing career.

Twenty years ago, he gained a wider listenership after the soundtrack for the 2005 Hollywood film Broken Flowers included his music, and the use of one of his recordings in last year's best-picture-Oscar-nominated Nickel Boys saw further interest.

But since the 1960s he has used the studio and rehearsal room as a laboratory where he has mixed musical styles to create what he calls the "science" of Ethio-jazz.

Outside, it was a cold November evening, but inside the West End venue, Mulatu was bathed in the warm embrace of a crowd eager to get one last glimpse of this alchemist at work.

Dressed in a shirt featuring work by Ethiopian artist Afework Tekle, he slowly and steadily walked on stage.

Squeezing past a set of congas he came to his signature instrument – the vibraphone.

Mulatu Astatke

Mulatu Astatke

In the studio and the concert hall, Mulatu has been working to create his Ethio-jazz sound

With two pink-felted mallets in his right hand and one in the left, he began to pick out the mesmeric rhythm and melody, expertly striking the xylophone-like metal bars creating a delicate, resonant sound.

The first song was based on a 4th Century tune from the Ethiopian Orthodox church.

It was a nod to his musical heritage and the Ethiopian pentatonic scale that gives his sound its unique flavour when combined with other jazz traditions from around the world.

"It was a beautiful show. Really enjoyed it," Mulatu told the BBC in his gentle voice after the concert.

But he would not be drawn on how he felt saying goodbye to his international fans.

For US musician and composer Dexter Story the gig was "bittersweet".

"It was so vibrant and so alive. A reverent and gracious… and wonderful, wonderful energy," he said.

"I'm very saddened that we won't have this genius… touring the world."

But his influence will live on in his recordings.

Mulatu Astatke

Mulatu Astatke

Mulatu has been making records since the 1960s

"My instinct when someone asks me to introduce them to Ethiopian music or to Ethiopian culture is to play Mulatu," says London-based fan Juweria Dino.

"They have listened to it all over the world," the musician said with pride. "They loved it. It was so beautiful."

He remains determined to promote music from Ethiopia and the wider continent which he feels does not get the acknowledgment it deserves.

"Africa has given so much culturally to the world. It is not being recognised as it should be recognised," he said.

His knowledge of life and culture beyond his home began at an early age.

Mulatu was born in 1943 in Jimma, south-western Ethiopia. As a teenager, his parents sent him to Lindisfarne College, near Wrexham in North Wales, to continue his education.

"I wanted to study engineering," he said.

But during his time there, Mulatu got drawn into the world of music, first taking up the trumpet. The headmaster at the time noticed his natural talent and eventually encouraged him to devote more of his energy to developing that gift.

"After I finished my school, they were telling me: 'Mulatu, if you become a musician, you will be successful.' So, I followed their advice. I went to Trinity College here in London."

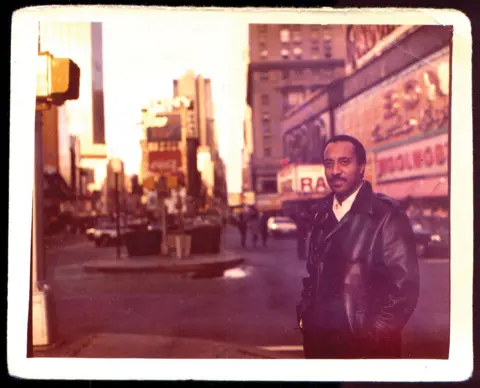

Mulatu Astatke

Mulatu Astatke

Mulatu toured the world - seen here in New York's Times Square in 1972

He remembers this period at one of the UK's foremost music colleges as a formative part of his journey. He has fond memories of jamming in jazz clubs with his musician friends.

"[Jamaican] Joe Harriot was one of the greatest alto saxophone players and we used to play together at a place called the Metro Club in London," he said.

To this day, Mulatu holds the UK close to his heart.

"To me it was so really great to be back again here."

In the 1960s, Mulatu moved to the US to enrol at Berklee College of Music in Boston – the first African to do so.

He studied vibraphone and percussion and began incorporating Latin jazz into his own music, recording his first two albums.

But it was only when he returned to Addis Ababa in 1969 that he created his own sound.

He changed the face of music at home during these "Swinging Addis" years. Using what he had learned at Berklee and combining it with Ethiopian modes, he "created this science called Ethio-jazz", Mulatu said.

Initially his radical sound was met with complaints.

"I remember them telling me 'get off, stop, stop there'. Because they don't understand."

But the resistance did not last long and his influence quickly grew.

In 1974, after Emperor Haile Selassie was deposed in a coup, many musicians left the country, but Mulatu stayed in Addis and kept making music.

Throughout his career, his deepest inspiration came from traditional musicians back home, who he calls "our scientists".

His tracks weave together traditional instruments from his homeland like the washint (flute), kebero (drum), and the masenqo, a single-stringed fiddle.

Mulatu describes the masenqo as sounding exactly like a cello.

"But the question is, who came first? Was it the cello or the masenqo?" he asked.

"The problem is we don't do research. We have so many great scientists in Africa. Great people, geniuses, who created all these instruments. But we don't give them credit."

Today, he says his mission is to broaden the range of the traditional instruments of his homeland by "computerising" the sound.

For his fans, it is his unique blend of the modern and traditional that makes Ethio-jazz so special.

"It reminds me a lot of music from South Asia, melded with the pentatonic scale which reminds me more of Arab music, along with the African percussion sounds that come through," said concert-goer Joseph Badawi-Crook.

"It's a completely unique mix and I just fell in love with it years ago."

Mulatu's legacy spans generations.

"Some of our grandparents or our parents or our aunts or our uncles, have seen Mulatu throughout his career," said London-based Ethiopian fan Solliana Kineferigb.

"To also be part of the younger generation and to have the opportunity to still see him live is amazing."

While the touring may be over, Mulatu pledges to continue to bring Ethiopian music to the world.

"It's not the end," he said.

More about African music:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC

14 hours ago

8

14 hours ago

8

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·  French (FR) ·

French (FR) ·