PROTECT YOUR DNA WITH QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY

Orgo-Life the new way to the future Advertising by Adpathway Photo of Poniatowska by Pedrobautista – Own work, CC BY 3.0

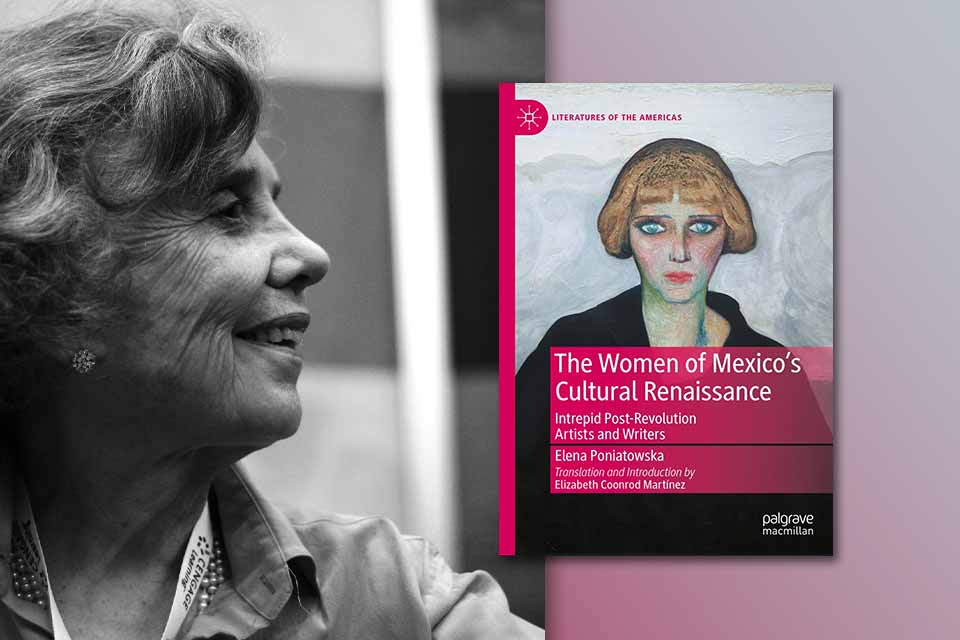

Photo of Poniatowska by Pedrobautista – Own work, CC BY 3.0

Las siete cabritas (2000), the literal translation of which would be “The Seven Little Female Goats,” is the original title of the book by Elena Poniatowska (b. 1932) that Elizabeth Coonrod Martínez has skillfully and delightfully translated as Women of Mexico’s Cultural Renaissance: Intrepid Post-Revolution Artists and Writers (Palgrave Macmillan, 2023). Coonrod Martínez explains that the Pleiades can be known as Las siete cabritas, and she writes that the constellation is appropriate for portraying “women as guiding stars for other women” (7). Apparently Poniatowska was not considering the “stubbornness” of goats when she decided on the title but instead “thinking only in terms of astronomy, noting that her husband, Guillermo Haro, was an astronomer” (7n8). Poniatowska’s depictions of seven writers and artists demonstrate that strength and perseverance must be model traits for women whose accomplishments often come at high costs because they are achieved in the face of dismissive, restrictive, corrosive, and sometimes deadly patriarchal norms.

The seven main chapters of Women of Mexico’s Cultural Renaissance delve, respectively, into the work and lives of seven Mexican women who, except for Frida Kahlo (1907–1954), are likely unfamiliar to English-language audiences. In addition to Kahlo, who appears first, they are: María Izquierdo (1902–1955), Nahui Olin (Carmen Mondragón) (1893–1978), Pita (Guadalupe) Amor (1918–2000), Elena Garro (1916–1998), Rosario Castellanos (1925–1974), and Nellie Campobello (1900–1986). Coonrod Martínez adds an introduction and an essay titled “Legacy and Biography of Elena Poniatowska” to the original text. (Las siete cabritas also includes terrific photographs, some by Kati Horna, that are unfortunately absent from the translation.) Coonrod Martínez’s introduction concisely provides relevant historical context, focusing on how women in the post-Revolutionary decades (the “Renaissance” of the book’s title) were “not acknowledged or permitted to participate in” the collective expressions of artistic ideas like the 1923 muralists’ manifesto and the 1938 manifesto about revolutionary art signed by André Breton, Diego Rivera, and Leon Trotsky (6). Women’s cultural and political marginalization went hand in hand. Denied the right to vote at the 1917 Constitutional Convention, women did not win the struggle for universal suffrage until 1953 (5–6). Four- to five-page biographical sketches of each artist, which Coonrod Martínez has also added to the translation, help readers discover related exhibits, literary texts, including translations into English, and scholarship.

The translation showcases Poniatowska’s vivid style, candor, remarkable research, and ability to write about her subjects with a rare combination of admiration, patience, understanding, and occasional exasperation.

Coonrod Martínez’s translation will impress readers both familiar and unfamiliar with Poniatowska because it showcases the latter’s vivid style, candor, remarkable research, and ability to write about her subjects with a rare combination of admiration, patience, understanding, and occasional exasperation. In “Legacy,” Coonrod Martínez’s details Poniatowska’s ability to achieve tremendous success in a milieu dominated by men, especially in the first decades of her career, which began in the early 1950s. Coonrod Martínez inspires her readers to learn more about Poniatowska’s work, including her vast number of interviews, groundbreaking work in testimonial and socially oriented literature, short stories, and novels. Especially connected with The Women of Mexico’s Cultural Renaissance are three biographical novels about additional mid-twentieth-century artists and writers: Leonora Carrington, Lupe Marín, and Tina Modotti, respectively.

Poniatowska writes with her subjects more than she writes about them. She transforms quotations from her sources—newspaper articles, diaries, interviews, correspondence, biographies, and perspectives from colleagues, friends, and family—into scenes that bring her readers into the artists’ lives and her own process. The seven chapters achieve this transformation in part because they often read like collages that also create compelling and coherent portraits. Poniatowska’s style underscores intersections, overlapping places and times, and incompleteness. She aims less to have the last word on her subjects than to present their careers and lives to her readers as, even after their deaths, works in progress to be interpreted and reinterpreted, all within the generative constraints of the historical and cultural context Poniatowska constructs.

A striking collage-like image appears in the chapter about Kahlo, the only artist Poniatowska portrays in the first person. A paragraph that presents an ordered sense of oneself in the form of a map—which for Poniatowska’s Kahlo locates pain in the north, love in the south, passion in the east, and affection in the west (64)—ends with an ironic observation about how work outlasts the artist (probably a nod to the eponymously authored “Borges and I”): “When my life is over—because it will end—I, Frida, will remain to immortalize her. I am one and my life is another” (64). This one-sentence paragraph is next: “I bury my hands in oranges” (64). The description of making the map is in the past tense. Frida’s efforts to immortalize herself are in the future. Her being and life are in the present, as is the moment of vitality (which stands out in contrast to the way “bury” implies death) when the reader imagines Kahlo’s hands in a bowl of brightly colored fruit.

Bringing Kahlo’s hands to the present reinforces their reliability. That which has “never failed” Kahlo are her hands: “they have followed my mind’s orders, while my entire body has betrayed me” (58). Her teeth, on the other hand, are a source of shame. “This woman you see, looking directly at you, is a deception. Beneath these lips that never smile are rotted, black teeth” (57). This interplay of revelation and concealment joins observation and introspection when Poniatowska writes, as Kahlo, “This woman you see, contemplating herself in the mirror, forever reflected in the other, on the canvas, in the windowpanes by which I travel outside in my imagination, this woman you see smoking, who comes forth from the canvas and observes you fixedly, is me” (58). Kahlo’s reflections mirror what Poniatowska does with her own writing: she creates the illusion of revelation and identity by acknowledging the centrality of artifice to artistic creation. Artifice in turn relies upon collaboration. Poniatowska places her writing within an essential collection of voices. Her hands, typing on a keyboard or holding a pen instead of a paintbrush, do not fail her either.

Poniatowska creates the illusion of revelation and identity by acknowledging the centrality of artifice to artistic creation.

The supports that enable Poniatowska’s insights include interviews she conducted. As Coonrod Martínez observes, Poniatowska interviewed all but two (Campobello and Kahlo) of her book’s seven subjects (53). In the chapter about Izquierdo, Poniatowska quotes the painter as telling her in 1953 that she owes “a lot” to the much better-known Rufino Tamayo, who was also Izquierdo’s lover, but that Tamayo also “owes” Izquierdo “a great deal” (86). Poniatowska combines firsthand accounts with those of others who knew Izquierdo well, including Juan Soriano and Luis Cardoza y Aragón. The chapter about Izquierdo demonstrates how Poniatowska’s book contextualizes its portraits of individual women within patriarchal contexts that place women at odds with one another. Izquierdo’s relationship with Tamayo caused Olga Flores Rivas, who married Tamayo after he and Izquierdo had split up, to forbid “mention of María for the rest of her life”; and, as Poniatowska continues, “the world obeys that request” (78). Patriarchal possessiveness pervades the group of artists to which many of Poniatowska’s subjects, and Flores Rivas, belonged. In 1929, when Rivera openly admired Izquierdo’s work, and only Izquierdo’s, in an exhibit at the Academy of San Carlos, the venerable art school Rivera directed at the time, it provoked frightening jealousy among her male classmates (72). In 1945, by contrast, Rivera was a gatekeeper who acted against Izquierdo, playing a role in the loss of a contract to paint a mural for the Mexico City government that Izquierdo had already secured (82).

Poniatowska’s collaborative style echoes the vibrancy of the groups of artists who helped or hindered her subjects.

Poniatowska’s collaborative style echoes the vibrancy of the groups of artists who helped or hindered her subjects. In addition to Rivera’s influence on Kahlo’s and Izquierdo’s lives are: Lola Álvarez Bravo’s appraisal of a photograph Edward Weston made of Olin (101); an image of Marín dancing barefoot with Soriano at a cabaret Amor frequented, which places Amor’s accomplished poetry within her jubilant and wildly eccentric lifestyle (125); a scene from 1958 when Garro, uninvited, escorted thirty Indigenous people into an homage to Rómulo Gallegos at the publishing house Fondo de Cultura Económica in order to bring attention to Mexico’s endemic land inequality (141–42); and the importance of Campobello’s friendship with Martín Luis Guzmán, whom she entrusted with papers given to her by Pancho Villa’s wife, which were instrumental to Guzmán’s Memorias de Pancho Villa (Memoirs of Pancho Villa) (177). Destructive and even fatal betrayals also characterize the artistic and literary scene that Poniatowska re-creates. These include: Ricardo Guerra’s refusal to publish his and Castellanos’s correspondence after her death, against her expressed wishes (155); and Campobello’s kidnapping by the husband of a former student (40), which led to her death, and about which nothing was known for years. “If Nellie were a man,” Poniatowska writes, “Mexico would never have permitted one of its novelists to just disappear like that” (195).

The Women of Mexico’s Cultural Renaissance exemplifies Poniatowska’s singular way of avoiding determinism while explaining how artists’ lives shapes their work. Her emphasis on strength, will, and perseverance—and an acknowledgment of the autonomy wealth can bring, as in the case of Amor—highlights the accomplishments her subjects achieved through their own efforts, often in the face of an openly hostile society. Several salient facts bring special brilliance and insight to Poniatowska’s portraits. Kahlo had only two solo exhibitions in her lifetime, one in Paris in 1939 and another at the Lola Álvarez Bravo Gallery in 1953. Izquierdo suffered a stroke in 1948 but continued to paint “with a bravery out of this world” (86). Olin’s paintings reached colorful heights during her relationship with Eugenio Agacino, a captain who died at sea in 1934. Amor wrote a highly acclaimed book of poems titled Yo soy mi casa (I am my home) and an autobiographical novel of the same title. Garro’s sense of who she was and her work was strongly shaped by fear: “there was always someone stalking: a man or a group determined to eliminate her” (134). Castellanos used Dolores Castro’s typewriter to write letters on the deck of the SS Argentina on her way to Spain in 1951, where, Poniatowska writes, “the great revelation for Rosario was of Saint Teresa” (161). Campobello published a poetry collection titled ¡Yo! in 1929 under the name from her birth registry, Francisca; and Langston Hughes translated some of the collection’s poems.

These and other details will motivate readers to follow the tantalizing paths they lay out, thus continuing to add to the magnificent collage that Poniatowska has assembled and that Coonrod Martínez has wonderfully rendered in English.

University of Maryland

.jpg?mbid=social_retweet)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·  French (FR) ·

French (FR) ·