PROTECT YOUR DNA WITH QUANTUM TECHNOLOGY

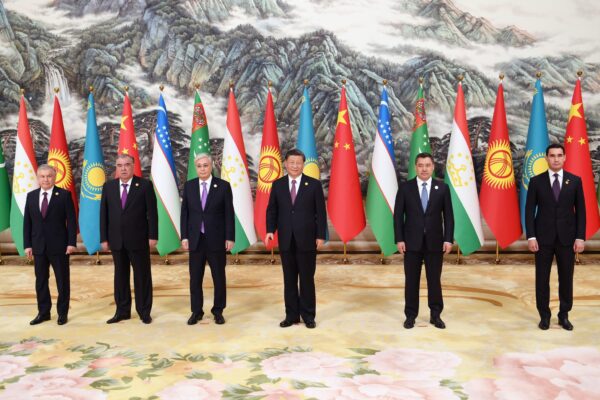

Orgo-Life the new way to the future Advertising by AdpathwayThe APEC (Asia‑Pacific Economic Cooperation) Summit in Gyeongju, South Korea, has gained international attention for its much-anticipated role as a venue for the leaders of the world’s two most powerful countries – China and the United States – to have a bilateral summit. The Gyeongju APEC Summit is the only major multilateral forum this year with both U.S. President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping in attendance, as Xi decided to not attend the ASEAN and the East Asia Summits held in Kuala Lumpur recently.

But beyond the Trump-Xi summit, APEC has a lot to offer to the free and liberal international trade architecture.

The global economy is facing a period of protracted weakness. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), global GDP growth is projected to slow from 3.3 percent in 2024 to 3.2 percent in 2025 and to 2.9 percent in 2026. Key contributors to the slowdown include higher tariffs, tighter financial conditions, elevated policy uncertainty, and faltering business and consumer confidence.

In particular, China’s economic growth is expected to moderate (from around 5.0 percent in 2024 to 4.7 percent in 2025 and 4.3 percent in 2026) and U.S. growth is forecast to diminish sharply. Meanwhile, the World Bank reports that growth in the 2020s is likely to average only around 2.5 percent – the weakest decade since the 1960s.

Export controls, rare earths supply chains, technology decoupling, and geostrategic tensions all loomed large ahead of the APEC summit. These issues have ramifications for both APEC and its two leading members, China and the United States. Yet the expectation of a sweeping “grand deal” at the summit was always wishful thinking. The breadth and depth of the issues mean that parties recognize they are at the beginning of a long, incremental game rather than a one that can be won in a single breakthrough. In the end, Trump and Xi essentially agreed to pause the most hostile trade actions for a year – with no guarantees beyond that.

The hype around the China-U.S. bilateral summit risks drawing attention away from multilateral platforms – especially APEC. The regional body, which has long championed free and open trade and investment and deeper regional economic integration via business facilitation and economic-technical cooperation, now finds its role under strain as fragmentation and securitization intensify.

In 2018, for instance, APEC failed to produce a joint leaders’ statement due to sharp differences between major economies. Many feared that the growing China-U.S. competition would hamper APEC’s relevance. But APEC has continued to function, albeit incrementally, thanks in part to its institutional form. Its loose intergovernmental structure, plus its consensus-based and nonbinding modus operandi, may limit ambition but offers agility in a fracturing order.

That agility has allowed APEC to adjust its focus. Liberalization remains core, but newer dimensions such as sustainability, inclusivity, digitalization, and demographic change now feature prominently.

However, when it comes to the more contentious or structural issues – such as export controls, rare earths supply chains, Taiwan, and agriculture – APEC’s consensual, voluntary, lowest-common-denominator format is unlikely to deliver breakthrough outcomes. It won’t be the forum where major breakthrough solutions emerge. And no one seriously expects it to be.

Instead, progress is most feasible in areas of functional cooperation. For example, APEC ministers and officials have identified deliverables in food security, small and medium enterprises (SMEs), health, energy, finance, structural reform, gender inclusivity, and corruption. On the sectoral level, these are tangible, achievable commitments that can maintain momentum.

For the 2025 host, South Korea, the priorities were AI cooperation and responding to demographic shifts, such as aging populations and declining birth rates. South Korea’s stated thematic pillars for APEC 2025 – “Connect, Innovate, Prosper” under the overarching theme “Building a Sustainable Tomorrow” – reflect this.

This shift underscores how middle powers are increasingly stepping into leadership roles in multilateral spaces, taking agency to maintain the rule-based order even as larger powers contest it.

In other words, rather than wait for the big players to resolve everything, regional groupings and middle powers are exploring what they can do. This means shifting from big bilateral power politics to functional institutional architectures that can manage complexity, fragmentation, and uncertainty.

In the end, the Trump-Xi summit was promising, but the limitations are equally real. While bilateral diplomacy remains critical, the broader order is increasingly shaped by regional multilateralism and middle-power initiative. In a world where strategic rivalry, supply chain realignments and policy uncertainty dominate, institutions like APEC may not rewrite the big power script – but they can preserve spaces of cooperation, continuity and incremental progress.

For states and investors alike, that may be the most pragmatic horizon. This seems to be the current trend – middle powers increasingly leading the way. As South Korea’s report on the APEC Third Senior Officials’ Meeting and Related Meetings (SOM3) stated, “member economies [are] engaged in substantial discussions on developing new initiatives to replace long-term projects due to be concluded soon.”

While Trump and Xi might occupy the lion’s share of global attention, other countries, particularly middle- and small-powers are now taking the reins, utilizing their agency to maintain the rule-based multilateral order.

1 day ago

2

1 day ago

2

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  French (CA) ·

French (CA) ·  French (FR) ·

French (FR) ·